Racing towards a sustainable future

Motor sport and sustainability have long been intertwined, and innovations across the FIA’s championships are continuing to drive our technological future on and off the road.

Intense competition, rigorous standards of fair play, teamwork, entertainment, profit – for ‘big’ sport all of these are key elements in the battle for hearts and minds in a crowded arena. But for any sport to survive, there is a further imperative – that it operates within a framework of standards set by society. As a microcosm of the world at large, sport cannot stand outside prevailing societal agendas and must play a role in not only matching progress but also defining it. One of the biggest issues facing the planet today is that of sustainability. While the environment is a primary concern for many, sustainability is about more than just the world in which we live – it is also the sustainability of opportunity, endeavour and progress. It is an issue that the FIA globally – and in more targeted fashion through its Environment and Sustainability Commission – is committed to tackling as Commission President and former Mexican President Felipe Calderón attests. “The FIA, as an international actor, has both an opportunity and a duty to be directly involved in the global sustainability debate, together with its member organisations, partners and other external stakeholders,” he says. “The Federation’s contribution to automotive sustainability has already had a positive impact, and a significant amount of the technology and innovation seen in the car industry today has origins in motor sport.” Since its earliest incarnations, motor sport has been a key driver of technological progress – pioneering the development of disc brakes, semi-automatic gearboxes and active suspension systems among other technologies – but over the past decade the FIA has, via the regulations governing championships, specifically targeted increased road relevance through racing innovation and the resultant technology transfer. And the bulk of the innovation has been targeted at efficiency and sustainability. “To give an example, in Formula One the FIA’s vision of motor sport innovation driving road-relevant, sustainable technology stretches back to exactly a decade ago with the introduction in 2009 of the first hybrid and energy recovery systems in the sport,” explains Calderón. “Turning lithium-ion batteries from a pure energy storage device into a power delivery device was a technology breakthrough that rapidly began to yield rewards on the race track and whose results are seen today in high-performance EV cars.” The example is one being repeated across the FIA’s major championships with the result that FIA Deputy President for Sport Graham Stoker believes sporting engineering is increasingly at the forefront of the drive for sustainability. “We’ve got a remarkably successful story to tell because at its heart motor sport relies on efficiency,” he says. “Even the driving style of a top-level driver – be it in rallying, Formula One, or, in particular, endurance racing – it’s all about efficiency. It’s about correct lines, braking properly and looking after cars. “When you move onto the cars themselves, lightweight chassis are all about efficiency. Aerodynamics are about efficiency and then, when you come to the engine, the whole ethos behind the development of racing engines is that they’re meant to be efficient. That’s what it’s all about. It is, to me, an integral part of the sport that we need to tell people about. The central point is that any modern sport has to operate within the prevailing issues in society and, at the moment, one of the major issues is sustainability. We have to address this head on and it seems to me that if we do that and show we’re contributing, then we protect our sport.”

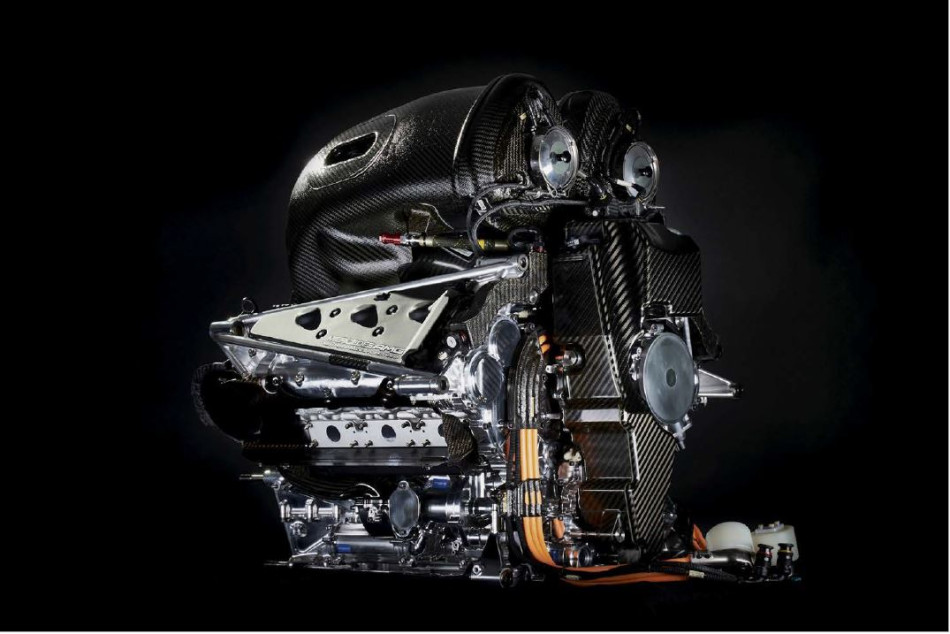

The all-electric FIA Formula E Championship has been a standard-bearer in the drive for innovation since its launch in 2014. The world’s first international electric-powered single-seater racing series, Formula E has been a proving ground for the evolution of battery technology. In its early years, each E-Prix would feature a car swap. But in Season 5 of the championship, Formula E was able to feature an electric car capable of completing a full race distance – and with a 50kW increase in power to 250kW. Cars are now powered by second-generation batteries with nearly double the storage capacity of the previous model, a technological development that is making its way onto the road. During the 2017/18 season, Formula E secured ISO 20121 certification for running sustainable events, becoming the first motor racing series in the world to do so. The series has partnered with the United Nations’ Environment Programme to improve air quality and is working on becoming a no single-use plastic event. For the eight major automotive manufacturers involved in the championship, it is the series’ potential to act as a technology lab that lies at the centre of Formula E’s attractiveness. “As a team we have a philosophy – race to innovate,” says Jaguar Racing team principal James Barclay. “That stands for a number of things, but key to it is the transfer of technology from the race track to the road and then back to racing as well. “We’re quite early in the development of this technology and, while the hardware might not be exactly the same as what you drive on the road, what we’re working with are components, so for example you’re trying to go as fast as you can for as long as you can with the battery. That’s really relevant learning to apply to a road car.” Formula E launched in the same year that F1 made the move to its current powerplants, with highly-advanced 1.6-litre V6 turbocharged power units replacing the 2.4-litre naturally-aspirated V8 engines used since 2006. The current F1 hybrid power units produced by Mercedes, Ferrari, Renault and Honda are marvels of modern engineering. In 2019, F1 cars are producing more power and running at greater speeds over the same distance as they were in late 2013, despite using half the fuel.

F1 LABORATORY

Andy Cowell, managing director of Mercedes AMG High Performance Powertrains, is one of those responsible for F1’s leap in hybrid technology. For Cowell, it is motor sport’s endless pursuit of more – more power, more speed, more efficiency – that has been the greatest driver of advancement. “Formula One’s regulations regarding fuel flow rate control, rather than an RPM and engine capacity control, focus you completely,” he says. “You’ve got a certain amount of hydro-carbon energy going in and you will win races if you can turn more of that energy into useful propulsion. Whether it’s an electric machine or an engine ora horse, it’s all about propulsion. “It’s all about propelling the person and their goods on their journey,” Cowell continues. “That mindset is – I think – a key thing, and that’s where the engineers, the craftsmen, the technicians in Formula One are utterly brilliant at having a mindset of, ‘Yeah, that can be done. What we raced last weekend isn’t good enough for next weekend.’ Having the regulations set, where there’s a limited amount of hydro-carbons per unit of time and converting that into useful propulsion, meant that we chased everything. It’s this sort of obsessive, compulsive approach of, ‘Well, we did that, but we did that yesterday, so that’s old hat. What can we do tomorrow?’” For Masashi Yamamoto, managing director of Honda F1, whose 2015 return to Formula One as an engine supplier was in part a response to the challenge presented by the new power units, motor sport is an essential laboratory not only for developing technology but also for helping to develop staff. “It’s a useful laboratory in the sense that we can consider utilising some of the technologies to transfer to mass production,” he says, “but it is also valuable in terms of the development of our engineers.“ In addition, for Honda, Formula One is now becoming the place to gather together cutting-edge technologies that it has developed in fields other than the motor industry. For example, the last power unit update we brought to the French Grand Prix came about through a collaboration with engineers from the Honda Jet airplane division. “A useful side-effect of this crossover between various Honda divisions is the interaction and communication between engineers from different disciplines, which leads to fresh thinking and new technologies,” Yamamoto concludes. “Therefore, we think F1 is a precious laboratory for us where we can apply trial-and-error methodologies to very high-level technologies.”

LANDMARK GAINS

That high-level technology has resulted in landmark gains. Two years ago, just four seasons into F1’s hybrid era, Mercedes issued a statement that in a dynamometer test at its High Performance Powertrains factory in Brixworth, UK, its M08 EQ Power+ F1 power unit had recorded a thermal efficiency level greater than 50 per cent. For the first time a racing engine had produced more useful energy than waste energy. “The naturally-aspirated engines [V8s that preceded the current generation] started at about 29 per cent thermal efficiency,” says Cowell. “Fifty per cent translates into being able to go further on the same tank of fuel. So there has been a 20 per cent gain in just a few years.” These phenomenal gains, although aimed at the Formula One car, also have ramifications for the road. “Take the energy that’s in the mass and velocity of the car and put that in a storage device,” Cowell says. “Whether that’s the lithium-ion battery or an ultra-capacitor or a flywheel, store it and then release it. That knowledge transferred into the road car world means you can have a lightweight system which takes that energy from the mass and velocity of the car, stores it and then uses it to propel you along. And that means you don’t use energy out of either your fuel take or your battery to propel you back up to speed.”

Formula One is far from alone in advancing our hybrid and battery capabilities. The World Endurance Championship and its showpiece event the Le Mans 24 Hours was an early leader in hybrid engine technology. The TS040 LMP1 car designed by Toyota for use in the 2014 running of Le Mans directly influenced the development of the 2016 Toyota Prius, the world’s best-selling hybrid car. Work conducted by Porsche, Audi, Toyota and Peugeot on hybrid engines and energy recovery systems used at Le Mans has already trickled down to current road cars, much as windscreen wipers and seatbelts made their way from the Circuit de la Sarthe into common usage in years gone by. And according to Graham Stoker, even events such as cross-country rallies have a role to play. “Rally events are often run though sensitive country; they’re being sponsored by the tourist departments of central and local government. They are able to do that because they’re run in a sensitive and sustainable way, and they have huge, positive spin-offs. Whenever there’s a disaster around the world, the first people in there are in four-wheel-drive vehicles. There’s all this development that comes out of motor sport that’s got a positive message about it.” Through helping drive the technologies that power our transport, both private and public, motor sport has shown that it has a role to play in developing our future mobility. Whatever the challenges to come, mankind will need to maintain reliable and efficient means of transporting both goods and people. As a driver of efficient technology designed around the highest safety standards, motor sport is well-placed to play a central role in the development of a sustainable future. “Motor sport has a major contribution to make in the dialogue that’s going on at the moment and I think it’s rather exciting,” concludes Stoker. “It’s positive social change and it’s dealing with pressing issues in society. Sports have a fabulous role to play, but we’ve got this very special role – we’re able not only to deliver a sport that is empowering and very important to people, but also we can deliver technological change and contribute to the sustainability process.”

FULL EDITION OF AUTO#27 TO READ HERE

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter